Examining environmental problems and solutions through the lens of decision analysis is the focus Environmental Decisions Alliance.

What is decision analysis and why do we need it?

When we make decisions we are at the mercy of our minds. What we mean by that is that as humans we are prone to psychological biases that alter the choices we make. For example, when making a decision we often fix on the first alternative we have before us, known as anchoring, or we make a choice to continue to invest in what we have been doing because we have already invested so much doing it, known as sunken cost bias. These two are just a subset of the biases we face when making decisions. Understanding these processes, the description of how we actually make choices, is known as descriptive decision theory. It is an intensely interesting field of research delaying mainly with the lack of rationality we have when we make decisions and how this can be classified. Probably most famous is the work of Tversky and Kahneman on the heuristics of decision-making, which led to a Nobel Prize in economics in 2002. Two (of many) key insights from this work are that when we make decisions from intuition we are subject to many errors and that an awareness of these biases could improve the processes we use to engage people in decisions. These insights solidify the utility of structured approach to decision-making that attempts to avoid, as best as possible, some of these general pitfalls from descriptive decision-making. Such a rules based approach to decisions, or a set of norms for aiding the decision process is called Normative decision-making and is a second branch of decision theory that deals with defining how decisions should be made.

The practical application of this prescriptive approach is called decision analysis, and is aimed at finding tools and methodologies to help people and organisations make better decisions. It was pioneered by Professor Howard Raiffa an expert in managerial economic, business negotiation and Bayesian decision theory.

The framework of decision analysis can be thought of as a series of steps (see figure 1) each bringing to bear a suite of tools for defining the problem, modelling the system and finding potential solutions.

Figure 1 The decision analysis process

Context – knowing what decision problem we are tackling

The first step in good decision making involves defining what the issue is we are tackling and what decision problem is being addressed, identifying who needs to be involved, establishing scope and bounds for the decision, and clarifying who is the decision-maker. This is essentially the platform that helps guide the decision process, keeping everything on track and ensuring people are considering the same framing of the problem. An example might be scoping that the decision is to be taken only in one reserve not the entire reserve network, that we are trying to achieve outcomes for biodiversity, first nations, and mining, and that the decision will be taken over a 5 year management horizon.

Being clear about what do we want – our objectives

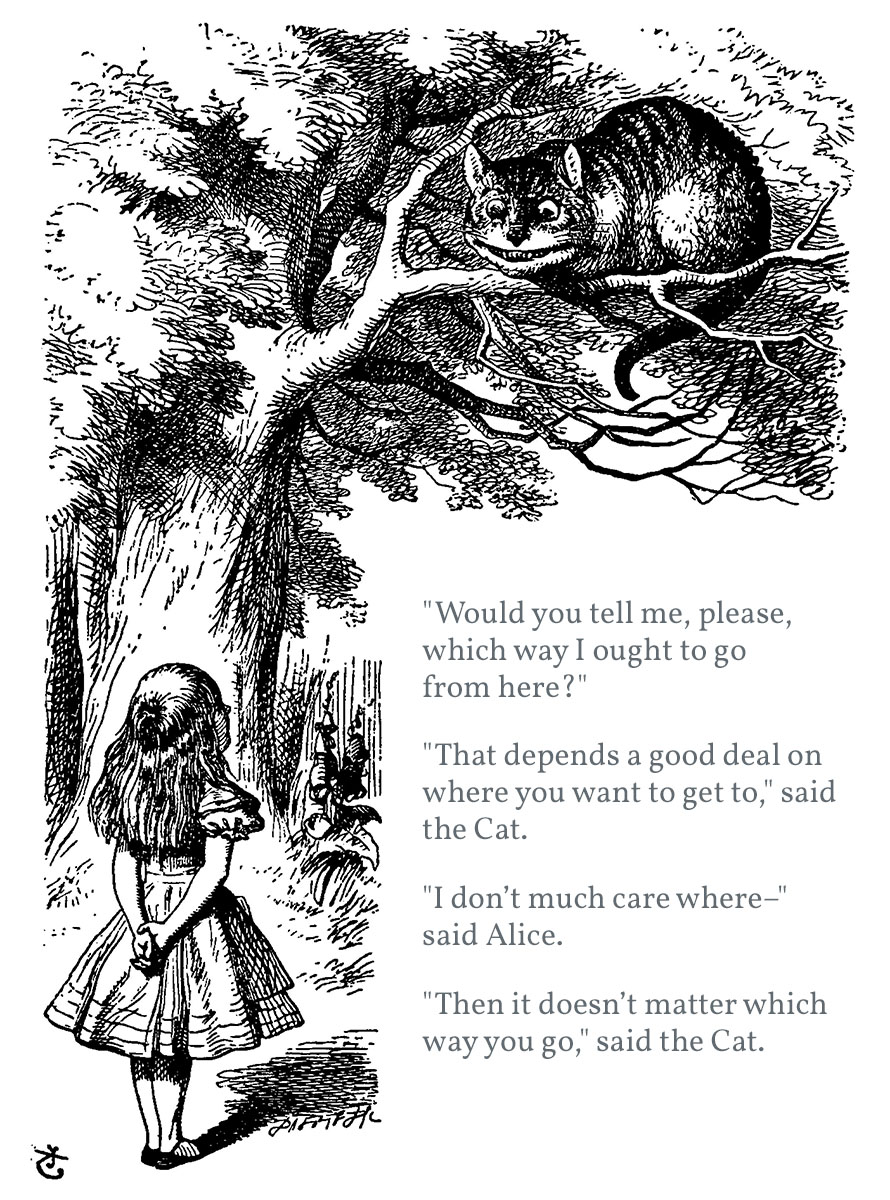

Figure 2 Objectives through the eyes of the Cheshire Cat

In Alice in Wonderland there is a fantastic moment between Alice and the Cheshire Cat which wonderfully sums up the need for objectives in decision-making (see figure 2). To surmise Alice asks the Cheshire Cat which direction she should go, in response the Cheshire cat asks her where she wants to get to, Alices says she doesn’t care, and the Cheshire cat suggests, quite rightly, that she has no decision to make, she should just go either way as she is sure to get somewhere. Essentially the cat is saying if we don’t have an objective – something we want to achieve – then our choice doesn’t matter. Restating in terms of decisions analysis we would say that if we don’t explicitly state what we want to achieve then we have nothing on which to compare our alternative decisions and we can’t decide is the best thing to do. This leads to the core of decision-making, which is a well-defined set of objectives and evaluation criteria for those objectives. For example we might want to maximise bird populations whilst minimising impact on mining revenue and first nation rights to land access. The set of objectives define fundamentally “what matters”, drive the search for creative ways to manage our system, and become the framework for comparing these things we could do.

Considering alternative things we can do

To strive for our objectives we need a set of alternative actions. At this point we are prone to biases limiting us to a small set of alternatives and stifling our selection of a good set of alternatives. What is needed here the development of a range of creative policy or management alternatives designed to address the objectives. A key point here is that our development of alternatives should not be limited by perceived constraints. For example saying an action is “too expensive” or “not likely to get community support” will minimise our ability to make true trade-offs later and reveal novel solutions to complex multi-objective problems. Instead these constraints should be captured in our objectives, such as “minimise cost” and “maximise community support”. Of course there are hard constraints, legalities for example, but by avoiding perceived constraints and allowing a creative process of alternative development we can build a set of alternatives that reflect different value positions or different priorities across objectives, and can present decision makers with real options and choices.

Evaluating consequences – connecting what we can do with what we want

Mapping our set of alternatives to our objectives is an analytical exercise in which the performance of each alternative is estimated in terms of the evaluation criteria developed in Step 2. This is where we evaluate the consequences of our actions towards what we care about. It is where the science really takes hold and the analytics begins. A broad set of tools sits within this step, from numerous modelling approaches, structured qualitative assessments and expert elicitation. Methods will vary depending on the connection being made, be they economic models, probabilistic models, spatial representations of the system, or models of human behaviour. The list is almost endless of approaches but the choice depends on how much time is available before the decision needs to be made, the complexity of the system and the specific consequences being assessed.

Making a decision considering trade-offs

Once the consequences of a set of actions is assessed it is important to work out which action best achieve our objectives. Decisions should not be a black box, and a process for allowing preferences to be evaluated and allowing trade-offs to be made is essential. A suite of preference assessment tools can be used to help illuminate preferences. Essential here is to understand that to assess our preferences we must do this based on the consequences of the actions within the context of the problem. What do we mean by this? If we asked you if you cared more about human health or old growth forest you may answer human health. But if we asked you if you cared more about 2 days of a mild cold or 1 million hectares of old growth forest, your answer might be different. How we feel about this question really depends on the consequences. Useful tools to aid in this process are swing weighting and Analytic Hierarchy Process. The preferences derived are then combined in an approach to select the best decision. Again there are many, including optimisation, cost-effectiveness analysis, risk assessment and multi-criteria decision analysis, the choice depends on the number of objectives, the level of uncertainty and how the decision maker approaches that uncertainty. The end point of this process is a decision or set of decisions that capture numerous objectives, and stakeholder preferences. From this a decision can be made and implemented.

Monitoring and learning to improve our decision

The last step in the decision process then is to identify mechanisms for prioritising information gain to reduce uncertainty and ongoing monitoring for future adaptation, reporting and guidance of future decisions. Here we need a set of tools that explicitly tackle the value of information for decisions and help prioritisation of monitoring actions. These include the economic theory of Expect Value of Information and adaptive management processes such as optimisation under uncertainty (e.g. partially observable markov decision process). The key here is to think about information in light of its role in the decision not just that more information is always better.